Artful is composed of four lectures Smith originally gave at Oxford, arranged inside a novel about bereavement. The lectures are assigned, in the novel, to the narrator’s partner, who has died a year before the novel opens. At the end of Artful there’s a section of color images: hence my interest in the book, for the Writing with Images project.

1. Images

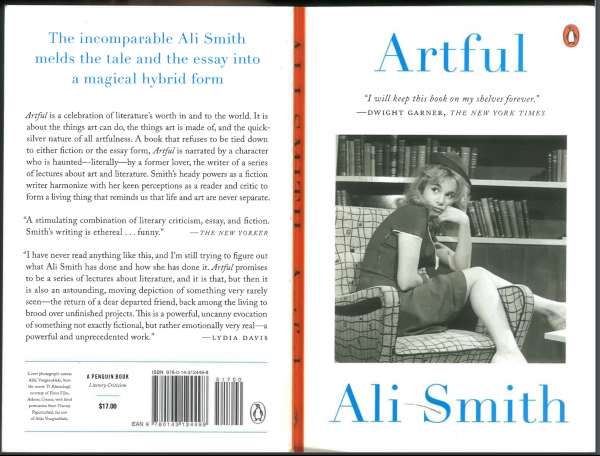

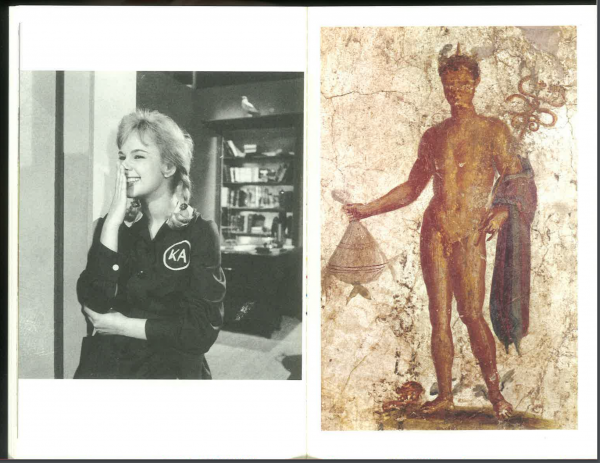

There are 16 full-page captionless color images at the end of the book. They are almost all of people and objects mentioned in the text. The Greek actress Aliki Vougiouklaki, who haunted the narrator’s partner’s imagination just as the narrator’s partner haunts the narrator, is the subject of one of the 16 photos, and she is also on the book’s cover.

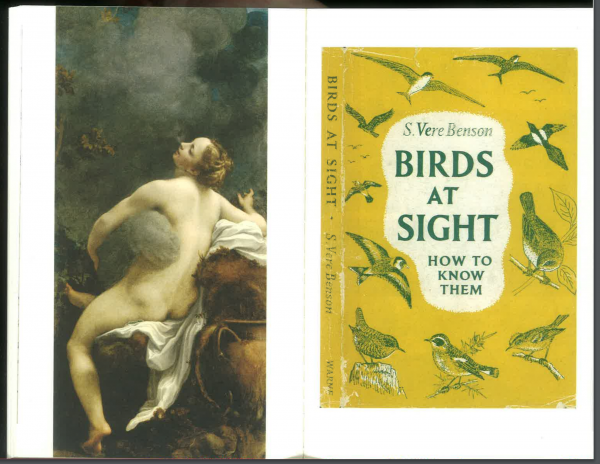

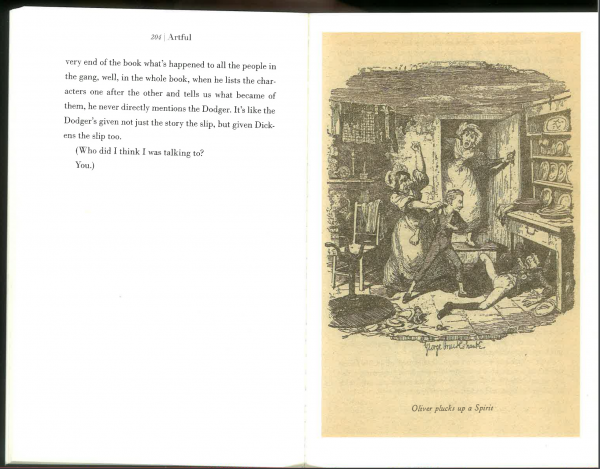

There’s a Correggio painting, the cover of a book the narrator’s partner’s ghost found in a bookstore, and two illustrations from Oliver Twist, subject of the first of the four lectures.

A reader who finds these after reading the book will recall the passages in which they were mentioned. But the pictures won’t, I think, add much to the reading experience. Their detail and color will be momentarily interesting, but the difference between their visual exactitude and the passing descriptions in the text will be enough to signal to a reader that Smith hasn’t really thought about creating a dialogue between text and images. The images aren’t used in the text: the people and objects aren’t described with the kind of specificity that would make it rewarding to turn back to check the relevant passages. The photos are an add-on, like a second thought: in my experience, a typical use of images in recent literary fiction. (And it’s equally typical that the images are scarcely mentioned by reviewers: fair enough, because they don’t need to be.)

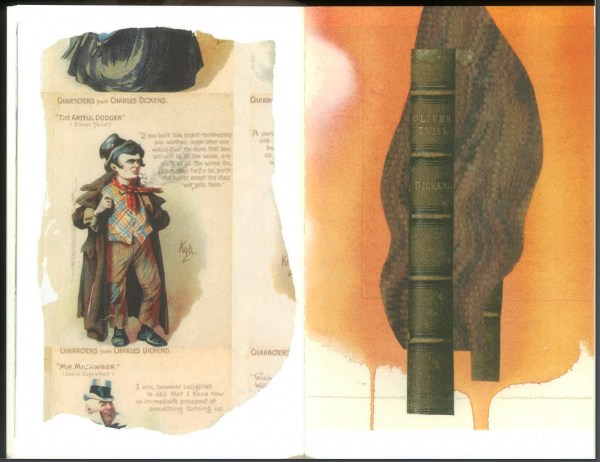

The last four images are collaged inventions based on a scan or photo of a spine of Oliver Twist. (This includes the right-hand image immediately below, and the image below that.) These are clearly by one person, and they’re clearly contemporary. The photo credits inform us that they’re by Sarah Pickstone. The fact that it’s necessary to turn to the photo credits to see who make the final four images is another sign that Smith hasn’t worked out what the images might do. Any reader who is attentive to these images will notice they’re by one person, and will be curious, and their curiosity will lead them out of the novel and into the back credit section.

The four closing images are not especially interesting or persuasive–they’re not on a par with Pickstone’s other work–and they do not add anything to the appearances of the book Oliver Twist in the other illustrations. The second, third, and fourth of the last four images propose that when Dickens’s book is cut open or otherwise broken, things can grow from it: either healthy trees (as in the image I’m reproducing above), or perhaps budding branches, or even bare trees with bloody branches. These suggestions are consonant with what happens in the narrative, but not illuminating: they don’t add complexity or interest, and as a group they’re anomalous because unlike the other 12 images they are presumably not things the narrator or her partner could have seen.

There is such potential in images in novels! So much could be done, even in Artful, with an artful use of images. I appreciate the exigencies of publishing, in which color inserts (often in multiplies of 8 pages, as here) have to be placed in one part of a book, rather than distributed throughout. But even with that restriction, how much more interesting it would have been to choose images only the narrator’s partner might have seen (like the cover of Birds at Sight, which the narrator’s partner reads in a bookstore), or only things the narrator might have looked up in her efforts to understand her partner (like the images of Vougiouklaki). These could all have been part of the ghost’s archive, or the ghost’s imagination; or they could have been the remnants the narrator is left with. There are many possibilities: it would also have been interesting to arrange the 16 images from clear to obscure, or from early to late, or from literature to life.

Instead the pictorial supplement is not even effectively an ornament to the text. For readers who stop to pay attention at all, the images are a brief distraction, and evidence the author wasn’t fully committed or decided about what pictures might accomplish, either in their individual meanings or as a collective ghostly appendix.

2. Problems mixing academic prose and fictional narration

Dwight Garner’s review provides the paperback with a front-cover endorsement: “I will keep this book on my shelves forever.” The context is Garner’s praise of a single line in the book (“Simile though your heart is breaking”). Garner likes parts of Artful, but he finds it flawed. The problem is that the lectures Smith gave at Oxford don’t always fit with the story of the narrator’s mourning. As Garner says, there’s a lot of dull writing here: not exactly academic, as he says, but poetically expository:

Edges involve extremes. Edges are borders. Edges are very much about identity, about who you are. Crossing a border is not a simple thing. [p. 131]

Sometimes the lectures seem padded; often they wander (for example, p. 124). This could have been made into a virtue. The narrator could have found some passages dull, and commented on the fact: that would have created an interesting distance between herself and the person she is mourning. But there’s also a simpler and more severe obstacle to taking Artful as it’s meant to be taken.

The narrator supposedly reads the four lectures after her partner has died, but it is consistently obtrusively apparent that Smith, not the narrator or her partner, is the author of the lectures. There are whole pages explicating poems and novels that Smith herself clearly wants us to know about (for example, p. 113). At one point the narrator is trying to read her partner’s handwriting:

The next page, which was the last page of [the lecture] On Form, had a scrawl on it, difficult to read. Did that say Italic? Italian? Cumin? Italian Cumin says near the end of his book… [p. 89]

“Italian Cumin” turns out to be Italo Calvino. This is okay if it’s supposed to be funny–if the narrator is kidding around–but not if we’re being asked to believe the narrator doesn’t realize, immediately, that the passage is about Calvino. The lectures reprinted and revisited in Artful are full of allusions and references, and the narrator knows basically all of them. It’s plausible she knows them because she was living with the person who wrote the lectures. But when we’re told she doesn’t recognize names or get allusions, it’s not believable. “You’d written about a man in a Greek myth, I couldn’t make out his name,” she writes on p. 146, but it’s hard to believe she doesn’t know, and in fact it’s nearly impossible to read passages like this and believe the narrator’s partner wrote the essays. Clearly Smith wrote them, and she needs to pretend someone else is reading them. It’s just as hard to go along when we’re told several of the lectures “break down” toward the end “into notes,” (p. 145) because we know from the acknowledgment in the front matter that the lectures were all delivered. These distractions are the exact opposite of artful as that word is usually meant: the elegant disguising of artifice, the accomplished simulation of reality.

Last, regarding the book’s models: there’s a curious passage on p. 85, in which the narrator reads about Sebald in one of her partner’s lectures. Austerlitz, the lecture she reads tells us, is

arguably his most novel-like novel, while simultaneously a work intensely uneasy with notions of fiction and with itself as fiction–in its most virtuosic [sic], most tortuous, darkest passage, an eleven-page-long single sentence about the concentration camp Theresienstadt… he uses simile only once…

What’s odd is the intensity of this passage describing the intense passage in Austerlitz. Nothing else in Artful is this intense, even though the description fits Artful better than any of the dozens of other literary citations. What place do “intensity” and parsimoniousness with tropes have in a book where an intense theme (haunting, mourning) combines with a fascination with similes (“Simile though your heart is breaking”)? Artful is didactic despite its author’s best efforts at melting her lectures into her novel.