[Since I wrote this, I discovered an interesting response to this project, and an extension to “audiovisual essays,” here.]

*

The little literature on narratives with images tends to go in one of two directions. Either it focuses on a single book or author, or it considers the concept of writing with images as a philosophic or conceptual issue. There is a need for a middle ground, a view of the subject that can discern practices and possibilities without descending to case studies or rising into generalities.

I have tried to do something like this for the simpler case of nonfiction writing where the illustrations are fine art. In that case I was thinking of art history and visual studies, and I had the idea that there are three normative ways images are used, and five unusual or experimental ways. Here are those eight points, abstracted from a long essay. After the eight I will propose some ways of looking at the same problem in the case of writing that is ambiguously fictional and nonfictional (for example, Sebald’s); and finally, in the curious case where the writing presents itself as fiction and yet includes photographs of real places and people.

A

Three Uninteresting Ways that Images Interact with Narrative in Nonfiction

First, visual studies and art history tend to use images as mnemonics, reminding readers of images they may not be able to recall with sufficient detail, or that they may have seen but forgotten. This is the usual function of images in art history, visual studies, art theory, art criticism, and related fields. The images are not supposed to be adequate representations: they do not fully represent what they denote, as the text does.

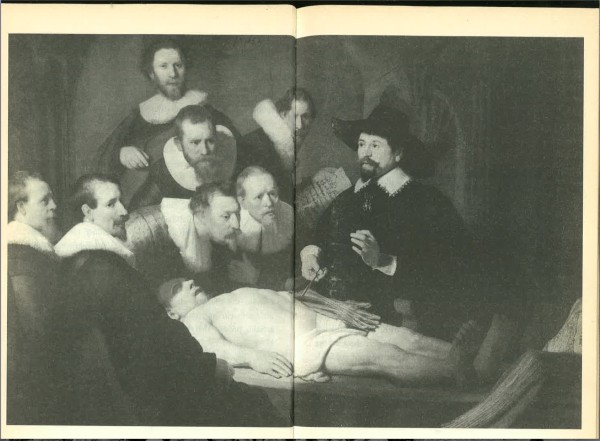

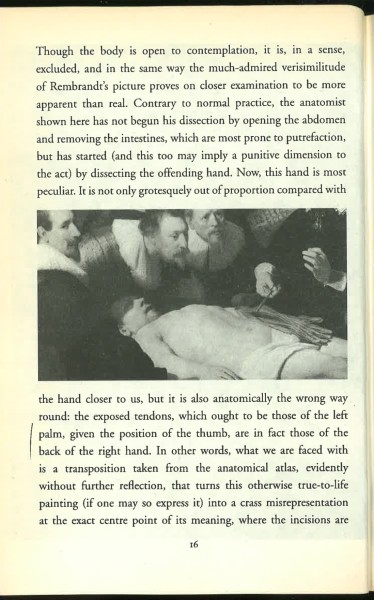

Second, visual studies and art history use images as examples of concepts developed in the accompanying texts. This is especially true of texts in which argument plays a large role: in art theory, for example, or in philosophy of art. This sometimes also happens in writing that is ambiguously fiction or nonfiction, for instance Sebald’s Rings of Saturn, where a Rembrandt painting is shown across a double spread, and then on the next page we’re shown a detail, exactly as in an art history text. (It is slightly differently placed in the German.)

The image serves as an example of a theory in the text (regarding truth, and the painter’s skepticism of “Cartesian rigidity”). (Incidentally, Sebald claims the tendons here are those from the back of the hand, and so they are deliberately shown incorrectly. There is a literature on this. He is probably wrong: these tendons resemble palmar flexor tendons; they are hard to dissect, and therefore they’re not always shown this way.)

Third, images are used as illustrations in both visual studies and art history. There is a distinction, I think, between examples and illustrations in this context: an example provides evidence or veracity to an argument; an illustration is an addition, an ornament, a conventional accompaniment. Images are often illustrations in more highly produced texts, such as coffee table books and exhibition catalogues. (It is pertinent that Sebald generally omitted photographs that would have been merely illustrations or examples; he preferred images that were pointers, that were suggestive, that moved beyond what the text spelled out. In art history, I think, that never happens.) (Searching for Sebald, p. iv-v = 507-8.)

The original essay I am sampling here is an introduction to a book called Theorizing Visual Studies; along with the other editors of that book, I proposed that images in the next generation of visual studies texts might function differently. Pictures might be less passive, and it might be possible for scholars to find ways to let images participate in the theorization of the field. We were interested in developing the claim, often made in visual studies, that images have their own power: that they contain or embody thought, that they have affective and cognitive power, that they can theorize or be considered as theories. I proposed five possibilities.

B

Five Interesting Ways that Images Interact with Narrative in Nonfiction

1. Images as intelligent theories: the photographs in visual studies and art history could function as theories alongside the positions and arguments adopted in the surrounding text. The principal example here is Leo Steinberg’s Leonardo’s Incessant Last Supper, which takes copies of Leonardo’s work as evidence of qualities and properties of the original, in the way that art historians have long taken textual responses to artworks as evidence.

2. Images as mistaken theories: if a visual artwork can be considered to be a theory about something, then it must also be possible for an artwork to embody a mistaken, impoverished, or misguided theory about something. If copies of Leonardo’s Last Supper can be what Steinberg called “intelligent copies,” then there must also be unintelligent copies, like this one:

As Karen Eliot pointed out, reading a draft of this chapter, there is a difference between “mistaken” and “unintelligent”: the former is entailed by theories that attribute propositional content to images, such as Nelson Goodman’s. The latter is, I think, the necessary unacknowledged opposite of Steinberg’s interest in “intelligent” copies. The Lego Last Supper might have nothing particularly “intelligent” to say about Leonardo’s painting, but it might not be “mistaken.” (See the full essay for more on this.)

3. Images as interruptions: images can be placed in texts in such a way that they interrupt ongoing arguments. This is ordinarily the case—we usually pause a moment when we turn a page and see a picture—but it can also be made part of the writing project. When I come to heading (C), writing that is ambiguously fiction and nonfiction, I will suggest that images can also be distractions: the difference is that in experimental writing, if an image is a distraction it is so intentionally, whereas in art history, if an image interrupts the argument, it does so because it’s placed in the middle of an argument—so it’s more an interruption than a distraction.

4. Images as things that remind us of argument: artworks have often seemed thoughtful, or have appeared to contain arguments or propositions. There are many examples in art history of accounts that treat images this way, including work by Louis Marin and T.J. Clark on Poussin. For both writers, in different ways, Poussin’s paintings conjure thought, embody propositions, argue, remind us of language.

5. Images as things that slow argument: reproductions in art history, visual studies, and related fields always present forms, colors, and content that is not directly related to the argument the author is making. That density of signs can also be made part of the writing project, when its effect—of distracting the reader, of slowing reading—is taken into account. My example here is Titian because I am thinking of Erwin Panofsky’s Problems in Titian: Mainly Iconographic, which is preoccupied with issues of narrative, reference, and symbol, even though the author says his book is black and white “not in spite of but because Titian was the greatest colorist of all time.” Detailed color reproductions in art historical accounts that concentrate on narratives and signs may function as impediments to efficient reading: we turn the page, see a gorgeous painting whose materiality is not at issue in the text, and we pause.

Those five positive and three negative possibilities are aimed at scholarly work on art; I think they can be brought forward, expanded and elaborated, so they can help describe what happens in the general case of writing with images.

C

How Images Work in Writing that is Ambiguously Fiction and Nonfiction

Here I mean writing that is “deeply invested in questions of fictionality,” as James Woods describes Sebald’s novels. There is no unproblematic way to characterize this writing, except perhaps in the negative: what concerns me here is writing that does not present itself as fiction or, unequivocally, as nonfiction. In the following section I will turn to writing that presents itself directly as fiction.

From this point onward, it may be best to say these remarks are on the ontology of images, because often the issue in fiction or work at the borders of fiction and nonfiction is the different relations between the reality shown us in images (especially photographs), and the reality proposed in the narrative.

Reading a draft of this chapter, Terry Pitts wondered if there is a place for images that seem to be inserted in order to insist on the veracity of what they represent. In that case, he says, “It seems to hardly matter if the author has ‘seen’ the newspaper clipping or portrait or whatever. It’s like slapping down a piece of evidence and saying to the reader ‘Look here!'” I think he is right, and it is largely Sebald who raises this issue, because in the indeterminately fictional and nonfictional context of his books, photographs of actual events anchor the narrative to truth and history in ways that the narrative does not. This is an under-theorized subject in the Sebald literature, because the ontological status of his images tends to be reduced to the idea that photographs are “indexical”—that they are realia, that they are taken as representations of the world.

It may be helpful to distinguish what Nelson Goodman called the “roots of reference” (here, the indexicality or reality of photographic representation) from “routes of reference” (“the various relationships that may obtain between a term or other sign or symbol and what it refers to”). (Goodman, “Routes of Reference,” Critical Inquiry, 1981.)

Sebald’s practice involves a number of routes of reference—photos he took, photos he manipulated, photos he found, photos of prints of landscapes, photos and Xeroxes of documents with representations, and so forth. Sebald preferred not to talk about routes of reference; he referred to the photographs in his books as merely “documents of findings.” (Interview in Searching for Sebald, p. 106.) This leaves the entire subject of the photographs’ presentation as Xeroxes, found images, or snapshots, and their quality and formatting in the books, to forms of reading that are not acknowledged in the texts. (As they are, for example, in Teju Cole’s work, where the narrator may refer to the image as image, and not only the image as document.)

For what I have in mind here what matters more is Goodman’s roots of reference. The photographs in Sebald’s books are intended to be signs of veracity, markers of the real, documents of events, proof of places and people. They are realia, interpolations of the real world into the text. In the usual cliché of photography theory, they are indexical, meaning they have a cause and effect relation to the objects, places, and people they represent.

This much is commonly known about Sebald and writers who have been influenced by him, and when the relation between photographs and text is put this way, it can apply as well to Breton, Rodenbach, and other earlier writers. It is possible, I think, to be more precise.

In particular it can be helpful to distinguish photographs that function as (1) anchors, (2) proofs, (3) distractions from the narrative’s fictionality, (4) testimony, and (5) evidence. There are interesting contingent distinctions between those terms.

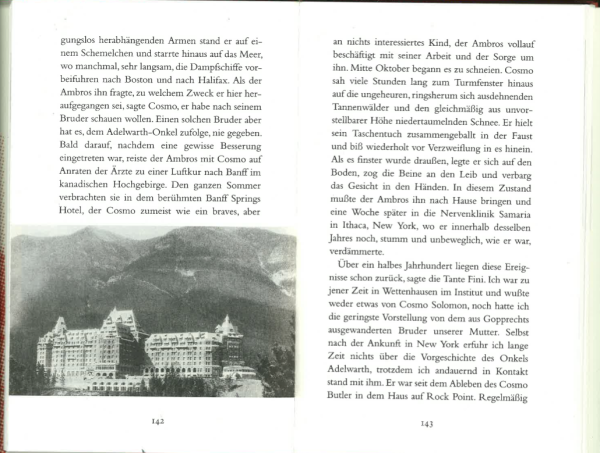

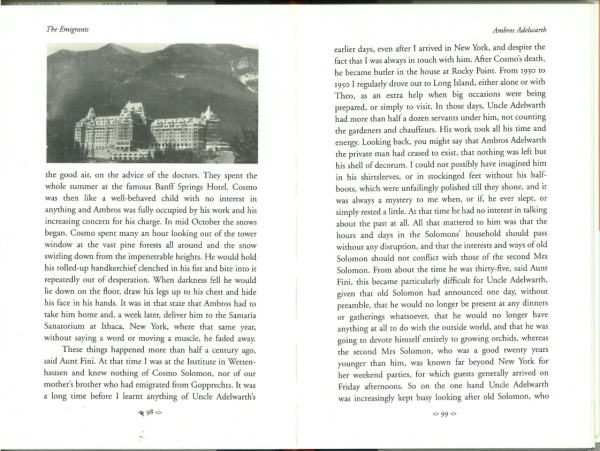

1. Here is an example of the metaphor of the anchor, from The Emigrants. The photograph shows the Banff Springs Hotel; notice how in both the German and English editions Sebald has been careful to place the photograph exactly two lines away from its identification in the text.

In Rings of Saturn, Sebald’s practice is to anchor his photographs to either the line of text just before or after the image, or the second line preceding or following the image. That close linkage puts the idea of fastening, anchoring, in a reader’s mind, as if the image needs to be tethered in order to function as a sign of the reality or truth of the narrative.

There are two issues interestingly entangled here. One is syntactic: it has to do with the relationship between the narrative and the images in the text; the other is semantic, because it has to do with the way the photographs anchor the narative in the real world.

Syntactically, it is curious that Sebald felt the need to put the references to his photographs so close to the photographs. In academic publishing, call-outs (“see Fig. 24”) do not need to be so closely matched to the position of the images. It’s as if he wanted readers to be able to move as easily as possible past the potentially distracting image.

Semantically, he needed his narratives to be interrupted by signs of the real, but he also needed them not to be interrupted too harshly: it’s as if the photographs had a power to disrupt or tear his narratives, and he needed to keep that power in check.

“Anchor” is a term used in word processing: bookmarks and other signs are fixed in place by nonprinting anchors. Just as there are no call-outs in Sebald, the anchors in digital texts are kept out of sight unless they are needed. Another term I might have used is “quilting point,” Lacan’s felicitous metaphor for the way that language can continue for long periods without being linked to the real. “Quilting points” are the places in upholstery where the couch is fastened to its wooden support; Lacan imagined language as a fabric intermittently fastened to the signs of the real. Quilting points might also be useful ways of thinking about how Sebald decided the dustance between his illustrations.

2. Photographs can also be ineffective, ambiguous, incomplete, or hidden proofs that things, events, and people actually existed. There is a potentially productive alternative between the use of images as proofs that something existed, and the cultural fact that photographs, in particular, are taken to be proofs that things existed. The first could be counted as a perlocutionary act, the second as an illocutionary act, in J. L. Austin’s terminology.

A perlocutionary utterance, in the 2018 Wikipedia entry “speech acts,” is defined as having “actual effect, such as persuading, convincing, scaring, enlightening…” If someone says, “I am scared,” the listener may try to comfort that person. What matters is the psychological effect of persuasion: there’s the photograph, so that person or place Sebald describes must actually have existed.

An illocutionary utterance has an “intended significance as a socially valid verbal action.” The utterance itself accomplishes the act, for example in the sentence, “With this ring I thee wed.” In Sebald, the image would be intended to be taken as proof—not only of the objects shown in the image, but principally of the people, places, and events described in the narative actually existed.

Sebald’s The Emigrants provides an example. The four stories in that book have widely been assumed to be “fictional or fictionalized sketches,” in James Wood’s words. But he reports that “Sebald told me in an interview that about 90 percent of the photographs were ‘what you would describe as authentic, i.e., they really did come out of the photo albums of the people described in those texts and are a direct testimony to the fact that these people did exist in that particular shape and form.'” (London Review of Books, February 20, 2014.) Wood adds the facts that “Sebald did indeed meet Dr. Selywn in 1970; Paul Bereyter was Sebald’s primary school teacher; his great-uncle Adelwarth immigrated to America in the 1920s; and Max Ferber’s life was closely modeled on Frank Auerbach’s.”

Even so, Sebald’s statement, presumably made in the awareness that it was for the public record, and Wood’s biographical information, do not prevent The Emigrants from being read as “deeply invested in questions of fictionality”: for me, the photographs produce the insistent but unclear claim that they represent something real. They are like illocutionary speech acts in that their mere presence is taken as proof; but they are like perlocutionary acts in that Sebald apparently intended that they help persuade readers of the truth of the text. (They do not work that way for me.)

3. When the images operate as proofs, they are also distractions from the fictional aspects of the text. This is why I like Austin’s distinction between illocutionary and perlocutionary speech acts: distraction is a temporary state, and a closer look can restore doubt or certainty.

Another way of looking at the images in Sebald’s book is to note that they also work as a whole: all the images in a given book can be understood to produce what Barthes called a reality effect. In an essay called “What Counts as True? Pictures and Fiction in W.G. Sebald,” Seth Kim-Cohen makes this point in relation to Austerlitz. “We are distracted,” he writes, “from the subjectivity of the testimony before us by the apparent objectivity of the photographs.”

The meaning of each individual picture is negligible. It is the meaning of the pictures’ collective presence, which is crucial to the functioning of Sebald’s books. The photographs say that the narrator, the writer (whoever), isn’t just making this stuff up. It’s out there in the world. The meaning of the photographs is that the objects in them are photographable: the buildings, the landscapes, the planes, the monuments, the trees, even the occasional person, exist. These photographs are admissible as evidence. [tinyurl.com/ncklgo8, 2011]

Sebald would probably not have wanted to think of his photographs as distractions, because the idea implies that in the end, the narratives are fiction, and the photographs only defer the moment that becomes clear. But because he needed so many photographs (more, for example, than Jacques Roubaud, or even Wright Morris) he must have also sensed that the photographs’ reality effect was not permanent, that it wore off as the reading proceeded.

4, 5. “Evidence” comes from Derrida’s Demeure: Fiction and Testimony. Derrida says that when testimony speaks, it insists “You must believe me, because you must believe me – this is the difference, essential to testimony, between belief and proof – you must believe me because I am irreplaceable” (Demeure, p. 40). Evidence, according to Seth Kim-Cohen, “calls for an unfiltered objectivity; a certainty upon which we can all rationally agree. Austerlitz, in particular, of all of Sebald’s novels, seems to want to present evidence rather than testimony.”

In Sebald, images seldom work as testimony in Derrida’s sense, because they do not plead or insist. He does not intend there to be any issue of belief: the fact that the images are monochrome and usually simply or even carelessly framed and presented is supposed signify that they are reliable representations of the world. When images are in the text mainly to insist on the veracity of what they represent, as Terry Pitts says, they can be testimony of some truth, of the idea of veracity, without being testimony of the particular objects or places they represent. In Derrida’s formulation, photographs like those are evidence. Yet at the same time, they are testimony if only because there are so many of them. Why repeat the claim of the real, unless the real is a matter of belief?

(Personally, I do not read Sebald for anything resembling truth: I read him as fiction, but that is another issue. I understand he wants some photographs to work as witnesses.)

As a postscrupt: an example of a book in which images work somehow against testimony and evidence, at least in my reading, is Jan Ramjerdi’s RE.LA.VIR (2000). This is a novel (as its subtitle declares), but it also testimony about a rape. The pages are full of sentence fragments, prompts and online artifacts (like >, —-, ❏❏, and lines like “ALT.RE.AL.E::EE:EPISTOL:://A.M.I./EE”), and the back cover opy says the story is told “through the narrative filter of an online hypertext program.” The text is relentlessly violent, pornographic, and obscene, a little like a combination of Kathy Acker’s Kathy Goes to Haiti and glitch art. But the photographs distributed through the book are almost all nude studies, in the manner of early 20th century classicizing photography from Stieglitz to Weston. The photographs are mostly set in a garden, and some even have classical columns. The effect, for me, is that the images help RE.LA.VIR to be what it says it is: a novel, rather than a traumatized confession ornamented with internet conventions. The pictures are anti-evidence, anti-testimonial.

D

Ways Images Work in Fiction

When the narrative presents itself as fiction, different issues arise.

1. Images can show us things the narrator sees. The most straightforward function of photographs, in particular, is to re-present to us things that the narrator is said to see. There are ramifying possibilities. The narrator can experience things immediately, as often in Sebald’s books, or see them in films or books, as in Bonnefoy’s l’Arrière-pays, where the narrator looks at pictures of places he has never seen.

2. Images can show us things the narrator has recently seen. This happens in Bruges-la-Morte when Hugues says he no longer needs to go out to see the places he’s seen Jane, and then we see a picture of such a place.

These categories are rich with variations. The example from l’Arrière-pays is also an example of this second category, because the narrator doesn’t say “I am looking at a travel magazine with a photograph of the Caucasus in it”: he implies he has seen such things in the past. The moment in which the author, Bonnefoy, goes and consults his travel magazine, and gives it to the photographer to be copied for the book, is outside the book’s narrative. Equally absent is any sense of how we are to imagine exactly what the narrator remembers of this photograph, if anything, when he writes about “their villages… often ruined,” without any further description.

3. Images can show us things the writer sees. Most of the pages in Anne Carson’s Nox are examples of this. Nox is presented as nonfiction, so the narrator is identified with the author, but even if it weren’t, the high-resolution color scans of documents and photos would necessarily seem to be things the author had seen. This may be a property peculiar to images, because even attempts at immediacy like the images and graphics in Tristram Shandy are distanced by the act of typesetting and printing.

Jesse Ball’s Census and Silence Once Begun are also examples of images as things seen by the author (as opposed to the narrator): there are many possibilities, which lead in different ways from immersion to metafiction and back.

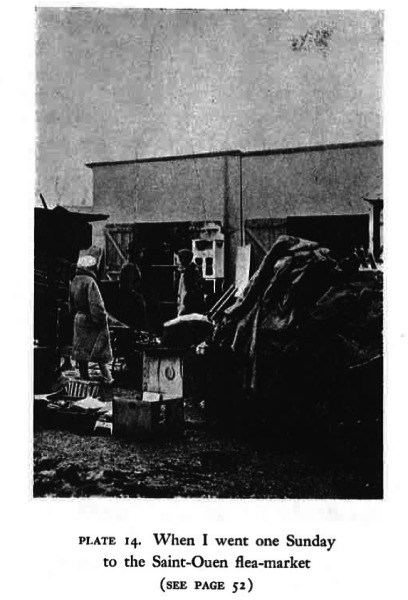

4. Images can show us things that are like what the narrator has seen. In Bruges-la-Morte, several of the city scenes are not described nor identified, and because the city is the image of his dead wife, those photographs may be taken as emblems or typical views of the city, like things Hugues has seen but not necessarily those exact things. In Breton’s Nadja, the scenes taken for Breton by Boiffard can be understood as resembling things the narrator and the author had seen.

(Presumably neither Breton nor his narrated character André saw those exact people, and so the scene at the flea market is intended to be similar to the episode recounted in the book.) Pitts, who read a draft of this list, pointed out that photographs can also be understood as emblems of a time or an era. That would be a generalization of photographs as images of things the narrator has seen, and at its limit it would also include things like those the narrator has seen. This happens, for me, with the images of the remnants of Ottoman life in Pamuk’s Istanbul. Many of these photographs are like things Pamuk had seen as a child, but most were gone before he was born.

I wonder if it might be interesting to distinguish these species of resemblance: an image that is very like something I have just seen, as opposed, perhaps, to an image that is fairly similar to a series of things that I have seen at various times in my life.

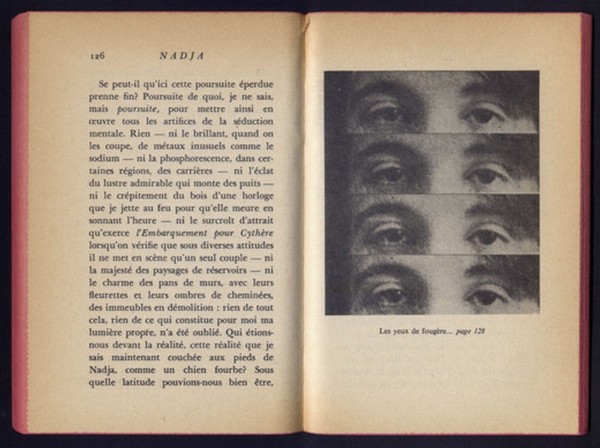

5. Images can show us things the narrator imagines. The narrator might imagine places she has never seen, or pictures she has never seen (this would include drawings, diagrams, anything at all). The collage of Nadja’s eyes in the 1963 edition of Nadja is an example.

What is the best way to think about what this image is? As a photo-collage, it may be understood as an approximation, in the medium of fine art photography, of the way the character André experienced Nadja; or it may be taken as an attempt to create an artwork that expresses a feeling, but not an imagined image, of Nadja. The difference is whether or not we are asked to imagine that André could have seen such an image in his mind’s eye. More on this at the end.

Pitts suggested as an example example flip-book at the end of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, which causes the falling man in the 9/11 photograph to float back upward, echoing the narrator’s wish that his father hadn’t died. Flipping those pages, a reader enacts the narrator’s desire, making it plausible that Foer intended the images as a picture—a moving picture—of something his narrator imagines.

There is an interesting ambiguity built into this: images may be presented as being imagined by characters, or they may be presented as representing what characters imagine. In the first case, as readers we would be invited to see mental images as the characters do; in the second case, we would be given completed pictures of things characters might experience differently. In the first case a character may think of an image in detail, and we’re invited to look at it along with her, even though it is in her mind’s eye; or a character may remember or picture something, and we are given a similar or typical image. The difference can be understood as a difference in the ontology of the image: in the first case, we are asked to think that the character experiences her life as pictures: a counter-intuitive notion, unless readers have eidetic memories.

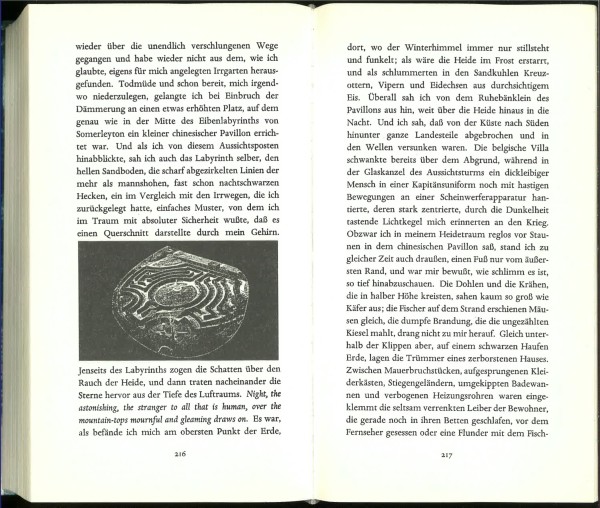

6. Images can show us things the narrator dreams. I know only one example of this, aside from the ambiguous and inexplicit ones such as the dreamlike images in Breton’s l’Amour fou, Nadja, or Bruges-la-Morte, which can be understood as hallucinations, daydreams, fantasies, or other signs of states that mingle wakefulness and sleep. The example is in Rings of Saturn, where an image of a labyrinth is something the narrator dreams:

It is interesting that this image doesn’t register as something entirely different than every other image in the book. It’s the only picture in the book that is not given to us as a picture of something in the world. It is followed by several unillustrated pages describing the narrator’s friend Michael Hamburger (the real-world author) describing, apparently truthfully, his memories. The fact that those 9 pages have no illustrations is also interesting, because if the narrator’s dream images can be illustrated, why not a character’s memories, which after all refer to real places? It seems that in Rings of Saturn, at least, the prohibition against illustrating things the narrator hasn’t seen is stronger than the rule that photographs should represent places and people in the world. And aside from all that, it’s curious that—at least for me—an image said to be taken from a dream is so easily accommodated in a book that is all about actual history—a book in which all other photographs are evidence. Surely that’s not just because of the cropping, which shows Sebald didn’t want us to see the details of the actual garden: it seems to be a property of the suspension of disbelief that I had never noticed before.

This anomaly, the single dream image, has not concerned commentators on Sebald so much as the image’s artifice. Lise Patt has traced the image to a tourist brochure of Somerleyton, and she demonstrates, in a photo-collage, how the image was cut from its page, laid on a Xerox machine with the cover up, and photocopied, producing a white ring around the image that ends up looking like a black paper mask:

But this belongs to a separate subject, because it is easily possible to imagine a dream image in this place in the narrative that was not modified in this fashion—it would have been enough just to declare it a dream image. The fact that Sebald didn’t speaks to the way he was imagining dreaming at that moment.

7. Images can show us things the narrator is unaware of. Any narrative that has an omniscient narrator should be able to accommodate photographs and other images of places, people, and objects that the narrator herself does not know about, or isn’t thinking about. Such images would be a simple structural parallel to the device of the omniscient narrator, or to indirect or free indirect narration.

I do not know any examples of this, except, as a precedent, the literally thousands of illustrated novels, novelizations, and retellings of operas, plays, and other stories in the 19th century, as they are exhaustively catalogued in Paul Edwards’s Soleil noir. The difference between those examples and the ones I am studying is that the authors of the books that concern me chose the images as they wrote; the texts Edwards studies often had images added after the fact, as illustrations of the stories—hence the fact that the characters are generally unaware of the pictures that accompany the texts. This category would overlap with the next:

8. Images can represent the mental states of characters. This, too, may be thought of as a logical extension of any narration that is intended to describe characters’ mental states. If a space exists for a narrative voice that can describe such states, then images should also be able to do so. (Needless to say images in the first few categories also go to the characters’ mental states; but I am thinking here of images the characters themselves do not see, remember, or experience.) Terry Pitts’s suggestion for this category is the film stills in Pierre Guyotat’s Coma, a book I did not find persuasive. Pitts proposes that because the stills “have nothing whatsoever to do with the direct narrative,” they might “be said to set a mood or represent some parallel to the text.” I think that is likely, but given the permissions and freedoms the author grants himself—it seems almost any visual material might have worked as well.

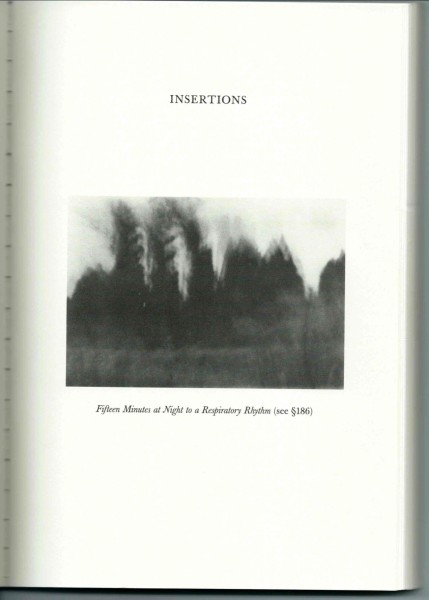

9. Images can represent the structure of the text. This happens with the two illustrations in Roubaud’s Great Fire of London, which are both images possessed by the narrator, but they quickly become available in the text as extended metaphors for the ways time and memory have been experienced by the narrator.

This photo, for example, is a blurred time exposure, taken at night, by the narrator’s wife; it comes to stand for her death and his insufficient memory of her. There is an important precedent for images that structure a text: frontispieces, which functioned as emblems and summaries of a book’s contents. There is a large literature on frontispieces, which could be brought to bear on this more recent history.

10. Images can break up the relentless drive of literary narrative. This radical position is Tan Lin’s; as he says in an interview, “eliminating images (or their mildly correspondent blank spaces with a text) would make reading more straightforward and linear, and for me, unrelenting.” I can’t think of any other examples of this aesthetic, although it is consistent with recent conceptual writing in general. It’s here just for completeness, and because of its fundamental place in the dynamic relation of words and images: the idea that images interrupt reading in some way is inherent to everything on this page, and in this project, and it can be traced to accounts like Jean-Francois Lyotard’s Discourse, Figure. At the moment, however, it seems to me that the use of images specifically to break up the normative flow of writing is rare, and may not necessarily be best thought of as an example of the much more foundational condition of writing and images.

11. Images can work against the veracity of the text. I suppose this entry really should balance the remarks under heading C, “How Images Work in Writing that is Ambiguously Fiction and Nonfiction,” because there images always have some function in relation to the real world. But it’s also possible, in fiction, that even photographs can produce an anti-realist effect. In Daniel Alarcón’s story “The Anodyne Dreams of Various Imbeciles,” the same photo is reproduced over and over, captioned as if it represented different people. The effect is to insist that the story is fiction, and to undermine whatever suspension of disbelief a reader might have mustered.

E

Beyond the Preeminence of the Text

The preceding ideas are all from the point of view of images, as it were, asking what images can contribute to narratives that are imagined as already in place, or as following historically delineated forms. And yet each one of them leaves the text preeminent. Even when an image is an “intelligent theory,” it is likely–as it is in Steinberg’s book–to be subservient to the text.

The most interesting texts are dialogic, by which I mean narrative and images that not only avoid the one-way flow of meaning characteristic of nonfiction texts with images, such as the ones at the beginning of this chapter, but also engage in a dialogue with one another, so that each is intermittently or consistently posed or personified as writing or text, each with its own interests and capacities for answering, overwriting, interrupting, and otherwise altering the other. Here are two examples of more dialectic exchanges, from the text’s point of view.

1. Ekphrases can balance images. The initial image of a hospital window in Sebald’s Rings of Saturn is matched, on the opposite page, by an ekphrasis describing what the narrator saw when he dragged himself to the window and looked out. That description takes about as much space as the photograph, and faces the image like a complement or discursive caption. This balances the reader’s attention, announcing—at the beginning of the book—that readers might pay equal attention to images and text. (Two more ekphrases follow before the appearance of the next photograph, which must also raise the question, in a reader’s mind, about a possible imbalance of words and images, an inadequacy of images, or an agon between what is visible and what can be put in words.) By the same logic:

2. Images can balance ekphrases. If a text has an extensive ekphrasis, and the image doesn’t correspond to it, then the image corrects or answers what’s in the text. It is possible–but very rare–that the image can then lead the reader’s imagination instead of the text.

3. Narratives can change images. In nonfiction it isn’t the business of the art historian or theorist to write about things that aren’t in the images, to remake the images, or otherwise to contradict what they reveal or represent. But in fiction things are different, and narrative has the capacity to overwrite images. Sebald does this in Rings of Saturn, for example where the narrator returns to the book’s opening image of an empty window, and says what he saw in it later: “I saw a vapor trail cross the segment [of sky] framed by the window” (p. 18 in the English edition). This is a striking strategy, because it puts a vapor trail in the reader’s imagination—in the reader’s memory of that image. It modifies the image without asking the reader to look at the image again, and so it declares, in effect, that the reader may hold the book’s images in her imagination, and expect the narrative to sometimes redraw them. By the same logic:

4. Images can change narratives. This, too, could lead to texts in which the images guide the reader’s imagination, and not the texts. But as in point 2, it is extremely rare. Both points 2 and 4 would require the text to have a quantity and quality of detailed references to the images, in order to compel readers to pay close attention, and not to skim or glance as we tend to do even with some of Sebald’s images. (Or with Tan Lin’s, for different reasons.)

There is a world of possibilities for writing with images in which the images lead: but it is, so far, almost entirely unexplored.