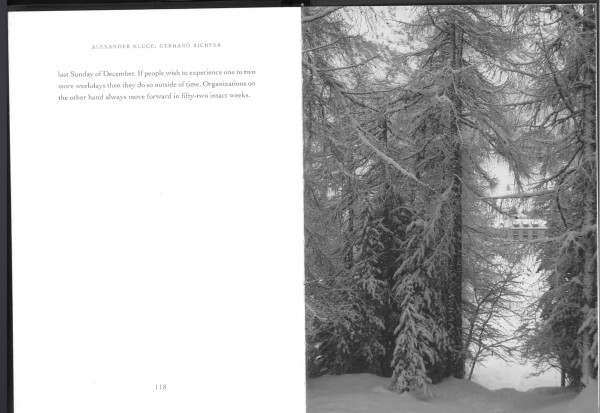

This is a short book with 39 photographs by Gerhard Richter and 39 prose pieces by Alexander Kluge, a German author and director who has also written books with illustrations. The photographs are all winter scenes. None have human figures; one has a deer (it’s shown below). At the end of the book the penultimate photograph shows a building that may be a hotel or lodge, and the final photo, at the end of the book, facing a blank page, is a road. (Both shown below.) The prose pieces are all dated, and range back and forth from the 19th century to 2009, with a focus on World War II.

(The original German edition is identical in layout. It only differs in its pagination—the text begins with page 7, following the German publishing convention—and in its subtitle, Ein Dezemberbuch, ein Buch zu Weinachten, ein Buch für alle Zeiten des Jahres [“A book for December, for Christmas, for the entire year”].)

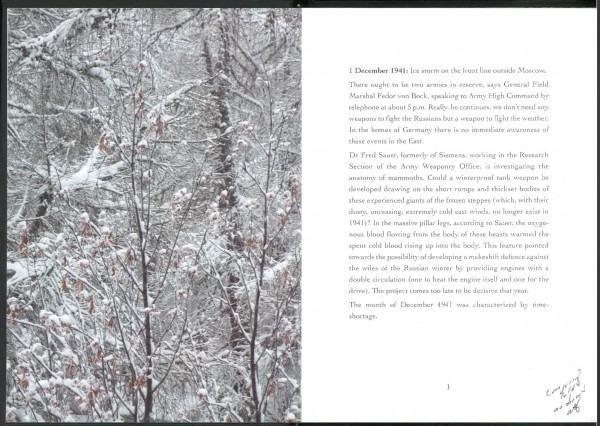

There is a tenuous, on-again, off-again relation between images and text. Kluge’s first piece opens: “1 December 1941: Ice storm on the front line outside Moscow.”

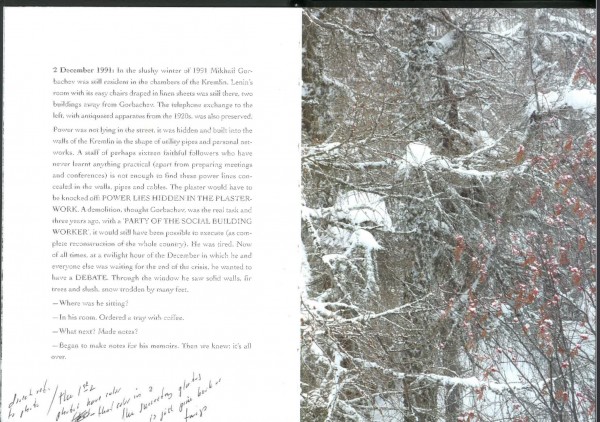

The photograph isn’t an ice storm, and a quick glance at the rest of the book tells the reader that the prose isn’t all about Russia. It’s more a conjuring of cold. Second photo and text are suddenly more closely related. Toward the bottom of the page we read: “Through the window he saw solid walls, fir trees and slush, snow trodden by many feet.”

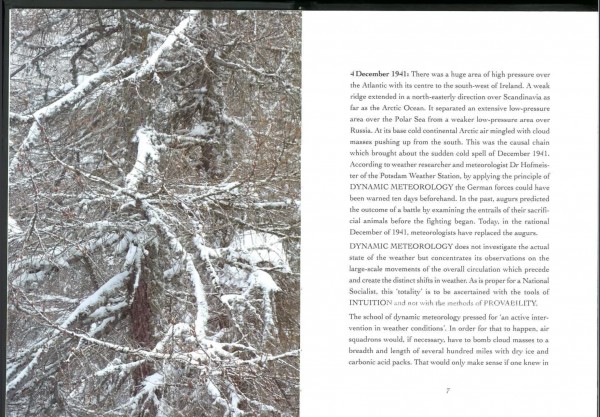

This uneven relationship continues throughout the book. It’s also signaled by the arrangement: the book opens with a photo on the left, and an image on the right; it continues with the opposite arrangement; and then there are two pages of text followed by the spread I reproduce below. The asymmetric, indifferent arrangement is also a sign of the variably independent voices of photographs and narrative.

Because any reader of this text will be familiar with Richter’s work, it’s reasonable to assume that it matters that the first two photos are the most colorful (they have reddish-brown leaves). A similar color recurs later where some recent-growth twigs show reddish, but mostly the photos are studies in grays and muted greens (the green of pine needles). That kind of limited palette is a familiar strategy in Richter’s painting series and his newspaper clippings, and there’s also the limited number of compositional types—so close that some photos at first appear to be copies of others. It also feels characteristic that the book ends with a scene implying photographer has emerged onto a deserted road. In short it can be read as a photo project, without the text.

Kluge’s text can also be read independently of the photos; it is a typical sequence of vignettes, sharply focused on historical moments, linked by unexpected parallels, by surrealist juxtapositions, and by the sense that continuous historical time has dissolved or fractured, leading to an increasingly painful awareness of history as an ongoing state of crisis. Richter’s resolute, depopulated, slightly varied scenes of bleak stasis are at first a kind of comfort against Kluge’s exploration of indeterminacy, bad luck, and historical catastrophe, but as the book goes on I think Richter’s sense of immobile history and suspended hope have less and less to say to Kluge’s dramatic fatalism. One of Kluge’s entries amounts to a concentrated (and wonderful) treatise on the violence of historical time: it’s about a man who can “hear time ripping,” and it serves as a metaphor for his entire text—but not for Richter’s photographs, which are seamless.

Sometimes it even seems the themes of winter and cold in Kluge’s texts are sops to their shared theme. It doesn’t help a reader’s confidence in the collaborative nature of the project that Kluge keeps setting his vignettes in wintry places (p. 44), or referring to wintry scenes in order to talk about such things as dead soldiers or cleared runways in wartime (p. 11). After a while snow and cold become expected or assumed metaphors, and therefore as quickly read or passed over as Richter’s photographs. A couple of times I noticed winter themes were absent, and that caught my attention as much as the evocation of snow or cold (pp. 51-2). In other entries Kluge develops the theme of snow much more deliberately even than Richter, provoking the odd thought that he was somehow competing with his collaborator. This happens, for example, in the extended entry on pp. 54-55 about the “THIRD POLE” over “the mountain massifs of the Great Pamir, Karakoram and the Afghan Hindu Kush.”

At one point Kluge tells a story of a doctor lost in the snow which parallels the two photos that Richer reproduces at the end of the book. It is an exceptionally long entry (pp. 58-61). It’s also one of the book’s more Sebaldian moments, in which melancholy is ornamented by historical specificity, in the way that Richter’s emptiness is decorated by the appearance of a lodge and a mountain road.

In the end December is not a model for writing with images, except in a very narrow way: it exemplifies the possibility that images might permit themselves to be overlooked—even the most devoted viewer of Richter will start leafing through the images at speed—in order to establish a contrast with a text that insists on its particularity, on the finite speed of attentive reading, and on a theory of discontinuity that is strongly at odds with the images.